La Niña possible, but not very likely

Climatologists, farmers, and other essential decision-makers are holding their breath as the potential development of a La Niña event hangs in the balance. The development of an La Niña event is on the caps to be decided.

For Australia, La Niña is often associated with increased rainfall, which can significantly impact agriculture and water resources. The uncertainty surrounding this event means that planning ahead becomes both essential and challenging.

Recently, the Bureau of Meteorology, keeping a close eye on the latest observations and modelling results, has raised its ENSO outlook to a La Niña watch, indicating a 50% chance that La Niña could develop in the coming months.

However, many are wondering why this La Niña signal is emerging so late. Typically, signs of ENSO events are observed earlier in the year, giving scientists and decision-makers more time to prepare for the associated impacts.

La Nina could be declared this summer

ENSO events have a well-documented history of triggering devastating global natural disasters. The 2015-16 El Niño, for example, affected nearly 60 million people across Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and the Asia-Pacific, leading to widespread droughts, floods, food insecurity, disease outbreaks, malnutrition, and respiratory issues.

Following the rare “triple-dip” La Niña from 2020-2023, Australia is bracing for the potential impacts of yet another La Niña event. The looming threat brings concerns of heavy rainfall and heightened flooding risks across the country.

Should La Niña be declared in 2024, it would mark the fourth ENSO event in just five years—an unusually active period for ENSO, though not without historical precedent. As Australia watches closely, the possible arrival of La Niña adds urgency to preparing for what could be another season of extreme weather.

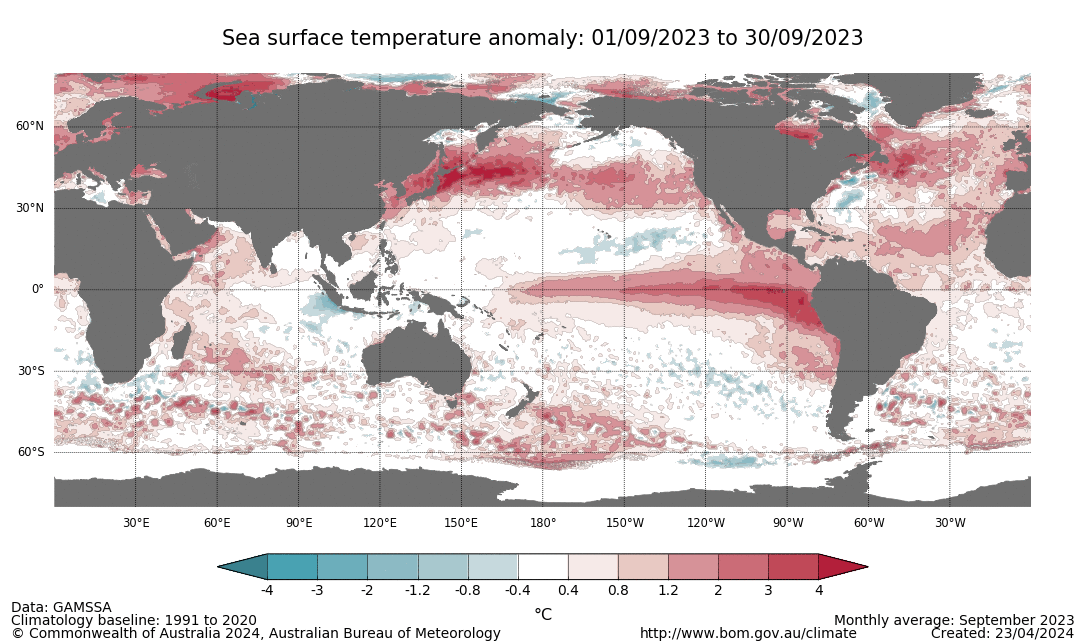

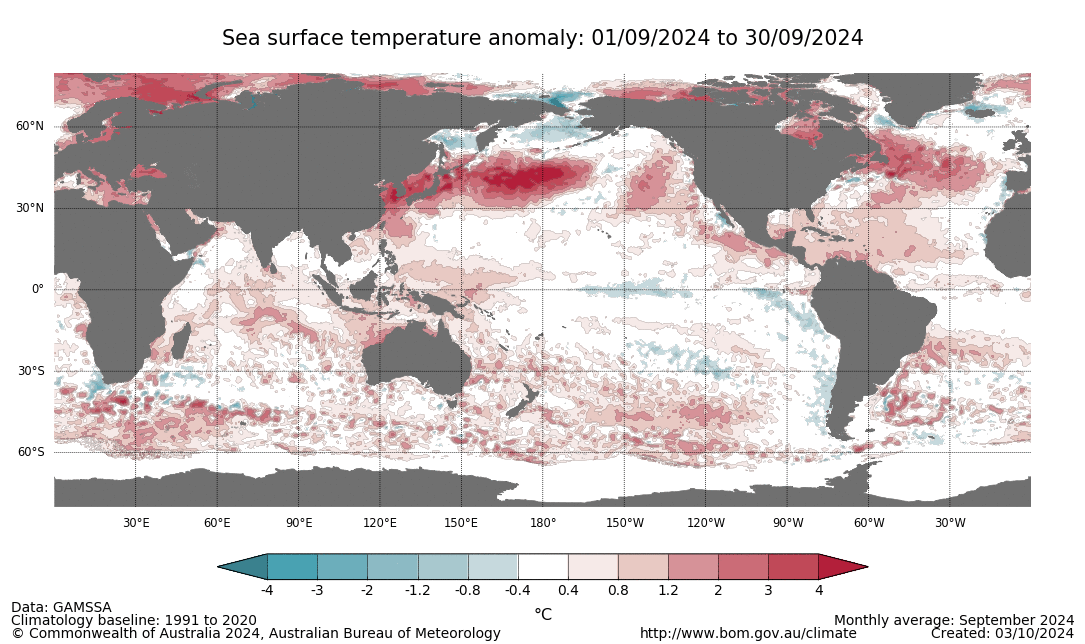

Example of September sea surface temperatures of 2023 versus 2024 based on the Bureau of Meteorologie http://www.bom.gov.au/

Late prediction of ENSO events- harder to predict?

Predicting ENSO events like El Niño and La Niña has always been tricky. These events follow the seasonal cycle, usually developing in autumn, peaking in late spring or summer, and weakening by the next autumn. However, predictions are hardest during the Southern Hemisphere’s autumn, a period known as the ‘predictability barrier,’ when forecasting accuracy drops significantly.

This year, we’ve reached late spring without a clear declaration of La Niña. Why the delay?

The Bureau of Meteorology points to climate change as a factor. Oceans have absorbed much of the excess heat from global warming, and warmer waters are being observed globally. This makes it harder to spot the specific warming patterns linked to La Niña, which usually causes wetter conditions in Australia.

The complexity of the ocean-atmosphere system adds to the difficulty. Even with improved prediction models, understanding ENSO still requires better data on deep ocean processes and how winds affect the system. Global warming may also be changing how often and how intensely these events occur.

More precise and earlier El Niño Southern Oscillation forecasts

A new study published in Environmental Research Letters has assessed the likelihood of different types of ENSO events—either in the Eastern or Central Pacific—occurring in succession. The results could lead to more accurate, long-range forecasts, giving communities additional time to plan and prepare.

By analysing weather observational records over the past 150 years and climate models, the research team was able to quantify the likelihood of ENSO events occurring in two consecutive years and examined the sequence of past El Niño and La Niña events of different types and identified clear patterns.

The study found that most El Niño events are followed by neutral conditions the next year, with a likelihood of 37–55.6%. However, La Niña behaves differently. There’s a 40% chance that a Central Pacific El Niño could follow an Eastern Pacific La Niña, and a 27.8% chance of two consecutive Central Pacific La Niña events.

“Australia recently experienced a strong Eastern Pacific El Niño starting in September 2023,” said Dr. Freund. “Our findings suggest only a 16.7% chance of La Niña developing in 2024, and if it does, it will likely peak in the Central Pacific.”

As climate change accelerates, the frequency, types, and transitions of ENSO events are expected to shift, with fewer calm, neutral years between events. The study indicates a greater likelihood of Central Pacific La Niña events following Eastern Pacific El Niño events, which may play out in the coming season.

Importantly, these results allow for more advanced ENSO predictions. Based on current conditions, the odds of an ENSO event can now be given up to a year in advance, providing valuable information to guide decisions. This helps identify not only what is likely but also what is unlikely to happen.

For the upcoming season, if La Niña does emerge, it is expected to be weak and short-lived.