Unraveling the history of El Niño flavours

After a strong eastern Pacific El Niño will we have a La Niña developing in 2024

Coral records from the tropical oceans reveal the first 400 year-long seasonal record of different El Niño events. This record shows an astonishing change of El Niño’s flavour in the most recent decades.

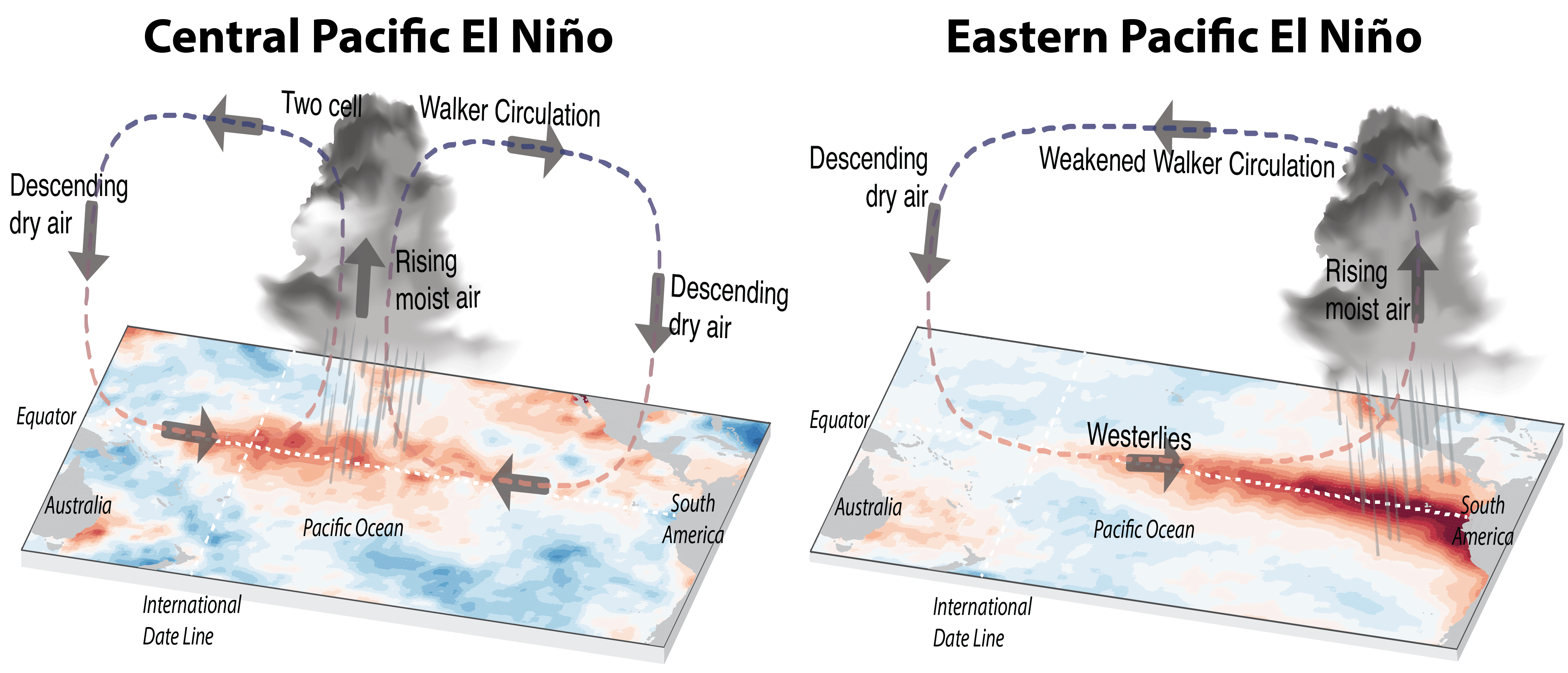

El Niño events can have many different characteristics and influence the lives of millions of people around the world. Over the past decades, considerable effort has been invested to study and describe El Niño events. However, how El Niño will behave with future climate change remains an open question. El Niño events already pose several challenges. At first, El Niño events are rather rare, happening approximately every 2-7 years. Only a handful of events have been directly observed since the advent of high-quality satellite imagery. A further complication is the fact that no two El Niño events are alike. Neither the initial conditions in ocean and atmosphere nor the impacts on temperature and rainfall, ecosystems, societies and economies are the same; they differ substantially. The complexity around those El Niño events has been slightly simplified with the recognition of different flavours of El Niño. Depending on where exactly the strongest sea surface warming in the tropical Pacific Ocean occurs, El Niño events can be distinguished into Central and Eastern Pacific type events. Still, the limited number of observed El Niño remains an issue.

By looking back, we can extend our record of El Niño events. This can better equip us understand current and future changes. Records from coral reefs are not only long enough to provide information about past ocean conditions, but also detailed enough to tell us about seasonal changes in the tropical Pacific. However, using coral records at seasonal scales is rarely attempted.

Focus on seasonal differences instead of annual averages

Scientists have previously used corals as silent archives of past ocean conditions. The hard skeleton of corals is built out of carbonates containing multiple elements including oxygen isotopes. Living corals incorporate these elements into their skeleton each time they grow, storing the chemical properties of the surrounding water at that time. During the course of a coral lifetime, the conditions that existed in its surrounding waters remain stored in their skeleton hidden in their growth bands. By measuring the chemical composition of these growth bands, scientists are able to retrieve the conditions that influenced its past growth. This can include information about rainfall, temperature or how salty the surrounding water used to be. Compared to trees which build similar growth rings each year, corals grow at a faster rate and can record oceanic condition at a much finer time resolution, ranging from biweekly to seasonal. These seasonal coral records have been collected from around the tropical Pacific by scientists across the world, involving decades of research, field trips and lab work. Our work has been made possible thanks to these efforts. By combining this network of corals records, we have been able to dig deeper into the common seasonal information stored in the corals and identify past El Niño events.

Prepared with an idea and preliminary results focusing on seasonal differences instead of annual averages, I presented this work to international experts. It was after this that Australian’s leading experts of past corals, Assoc Prof Nerilie Abram and Assoc Prof Helen McGregor, joint the team. Together with climate scientists, Dr Ben Henley, Prof David Karoly, and Dr Dietmar Dommenget, we worked out a way to identify and distinguish the different flavours of El Niño.

We found that a machine learning algorithm was the best tool for identifying the different flavours of El Niño. These days big data and machine learning algorithms are helping us in our everyday life. They are behind the next Netflix movie, advertisement or the automatic detection of holiday photos. Although used all around us, (earth) scientists are still hesitant to apply these algorithms to their data of the physical world.

In our study, a supervised machine learning algorithm has been applied to help to identify the different types of El Niño and importantly distinguished them from each other. Similar to a regression approach often used in sciences, a model is fitted to describe a process based on some known information. In our case, we can use observed sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific and know which years have been El Niño events in the central Pacific versus those in the eastern Pacific. Since 1950, we have observed eight Central Pacific El Niño events and eight Eastern Pacific El Niño events, but what do have all those events have in common? And more importantly, what distinguishes them from each other? Supervised machine learning can help us answer these questions.

Innovative big data & machine learning techniques

A supervised machine learning algorithm known as a decision tree, can find the underlying rules which lead to El Niño events. Similar to flowcharts or quizzes, like “what kind of Avenger are you?”, a decision tree finds consecutive paths which lead to a particular outcome. For example, your decision about the t-shirt colour, followed by our choice of superpower, may result in being more Captain Marvel than the Hulk. In our case, the decision tree describes pathways about sea surface temperatures in different seasons, resulting in either Central Pacific El Niño events, Eastern Pacific El Niño events or no El Niño. This novel method has the advantage of being able to identify and classify El Niño events very precisely. If the temperatures in the Pacific warm up during the summer and peak during Christmas time, we can detect an El Niño based on its seasonal evolution and where the warming started.

First seasonal record of El Niño activity

The first seasonal record of El Niño activity and our classification approach allowed us now to identify the El Niño events of the past 400 years. For the first time, with this extended information from the coral records, we can put recent changes of El Niños into a long-term context. Over the past 400 years, both the Eastern and Central Pacific El Niño events have occurred roughly at the same rate. By the end of the 20th century more El Niño tends to occur in the Central Pacific rather than the East. Additionally, fewer but more intense El Niño events happened in the Eastern Pacific.

Our results highlight the importance of long-term paleoclimate timeframes to assess and compare recent and future changes. The instrumental record is simply not long enough and El Niño events are too rare to fully understand the natural behaviour of El Niño.

This study could shed new light on the tropical Pacific and its decadal to multidecadal variations, as well as providing a new baseline to constrain and study El Niño events using climate models. An accurate simulation of both flavours of El Niño is a necessary step for climate scientist to understand the recently high abundance of Central Pacific El Niño events. Only with this understanding can we confidently predict future behavior of El Niño in a changing climate.